WGCDR Robert Henry Maxwell Gibbes 018233

DSO, DFC + Bar

| Squadron/s | 457 SQN 3 SQN |

| Rank On Discharge/Death | Wing Commander (WGCDR) |

| Nickname | Bobby |

| Mustering / Specialisation | Pilot |

| Contributing Author/s | Steve McGregor, Bruce Reid Updated by Vince Conant The Spitfire Association |

The funeral of Bobby Gibbes was held on Tuesday, the 17th of April, 2007 at North Sydney's St Thomas Anglican Church.

Mourners arriving at the church heard the throaty roar of the famous Rolls Royce Merlin engine before they saw the heart-stopping sight of a Spitfire in the burning blue sky above the church. It was a stunning sight as rare as the man who is our most decorated World War II ace fighter pilot.

CAF AIRMASHL Geoff Shepherd, CO 3SQN WGCDR Vinny Iervarsi, a 3SQN bearer and honour party and some 40 other members of 3SQN joined SQNLDR Gibbes' local member Bronwyn Bishop, and hundreds of other mourners in a fitting farewell to our Bobby Gibbes.

Four 2SQN F/A 18s flew a 'Missing Man' formation and the Temora Aviation Museum's Mk VIII Spitfire in the famous "Grey Nurse" markings of Bobby's own Mk VIII, flew a fly-past over the church.

In speaking of Bobby AIRMSHL Shepherd said: "Among the pantheon of the heroic generation from WWII, certain heroes stand out. Bobby Gibbes was one of those".

"It is an honour to have had him as member of the Services".

"Sadly this generation is quickly passing and we must engage and honour those who are left."

On the 5th of February, 1940 after the outbreak of WWII Bobby enlisted in the RAAF as an air cadet and after training was described as an “above-average fighter pilot".

Just how far above average is attested to by his Distinguished Flying Cross with Bar and Distinguished Service Order, though those who knew Bobby Gibbes well know he didn't see himself cast in the heroic mould.

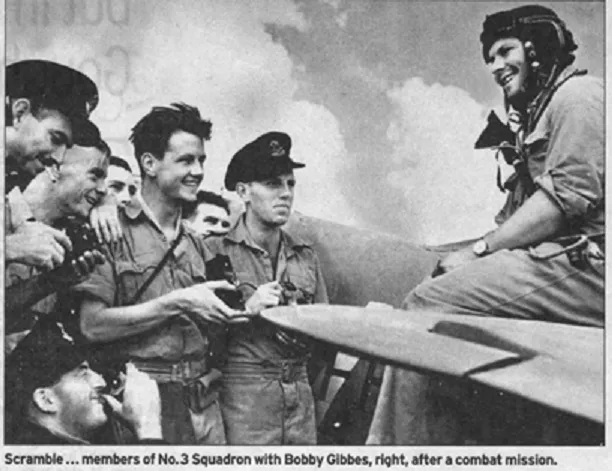

One who knew Bobby well is Ted Sly and Ted told the packed church that after training Bobby posted to 450 SQN before posting to 3SQN in Egypt flying the P-40 Tomahawk. In the North Africa campaign over the next two years he certainly saw and felt the heat of battle. He shot down or destroyed more than 12 aircraft, had up to another 14 probables and damaged 16. In return he was shot down twice.

Ted told of how Bobby made a landing in the heat of action and rescued another pilot who'd been shot down. On take-off Bobby lost a wheel but executed a flawless landing back at his home airfield. Though Bobby received recognition for this valiant effort Ted expressed his disappointment that Bobby was overlooked for greater decoration because he was a colonial. [See below] Ted told of another occasion where after being shot down, Bobby walked 50 miles back towards base, all the while dodging enemy forces until he was picked up by a British ground patrol.

After the commencement of World War II, No 3 Squadron sailed for Egypt, where, despite being heavily outnumbered, they provided air support to the 8th Army during the ebb and flow of the desert campaign. No 3 Squadron later participated in the liberation of Italy and Yugoslavia where the squadron was well regarded for its highly accurate attacks against enemy shipping. With a score of 217 enemy aircraft destroyed, No 3 Squadron remains the highest scoring fighter squadrons of the Air Force.

[Bobby writes:] ...Sergeant "Stuka" Bee's aircraft was set on fire by the aerodrome defence gunfire. As Sergeant Bee had a lot of speed from his dive and was flaming badly, I advised him to climb up and bail out instead of trying to belly-land his aircraft at high speed. He mightn't have heard me, or perhaps was badly wounded or even dead, as his speed had not decreased when he hit the ground. His aircraft rolled up into a ball, an inferno of flames. He didn't have a chance.

I circled and watched the Italians, showing great courage, send out an ambulance in an attempt to save him, but the outcome was obvious. It was later confirmed that he had been killed.

At the same time, Pilot Officer Rex Bayly called up to say that his motor had been hit and that he was carrying out a forced landing. Rex crash-landed his aircraft nearly a mile from the aerodrome, and on coming to a stop, called up on his radio to say that he was O.K. His aircraft did not burn. I asked him what the area was like for a landing to pick him up, and ordered the other three aircraft to keep me covered and to stop any ground forces coming out after him. He told me that the area was impossible, and asked me to leave him, but I flew down to look for myself. I found a suitable area about 3 miles further out and advised Bayly that I was landing, and to get weaving out to me.

I was nervous about this landing, in case shrapnel might have damaged my tyres, as on my first run through the aerodrome, my initial burst set an aircraft on fire. I had then flown across the aerodrome and fired from low level and at close range at a Savoia 79. It must have been loaded with ammunition, as it blew up, hurling debris 500 feet into the air. I was too close to it to do anything about avoiding the blast and flew straight through the centre of the explosion at nought feet. On passing through, my aircraft dropped its nose, despite pulling my stick back, and for a terrifying moment, I thought that my tail plane had been blown off. On clearing the concussion area, I regained control, missing the ground by a matter of only a few feet. Quite a number of small holes had been punched right through my wings from below, but my aircraft appeared to be quite serviceable.

I touched down rather carefully in order to check that my tyres had not been punctured, and then taxied by a devious route for about a mile or more until I was stopped from getting closer to Bayly by a deep wadi. Realizing that I would have a long wait, and being in a state of sheer funk, I proceeded to take off my belly tank to lighten the aircraft. The weight of the partially full tank created great difficulty, and I needed all my strength in pulling it from below the aircraft and dragging it clear. I was not sure that I would be able to find my way back to the area where I had landed, so I stepped out the maximum run into wind from my present position. In all, I had just 300 yards before the ground dipped away into a wadi. I tied my handkerchief onto a small camel's thorn bush to mark the point of aim, and the limit of my available take off-run, and then returned to my aircraft, CV-V, and waited.

My Squadron's aircraft continued to circle overhead, carrying out an occasional dive towards the town in order to discourage any Italian attempt to pick us up. After what seemed like an age, sitting within gun range of Hun, Bayly at last appeared, puffing, and sweating profusely. He still managed a smile and a greeting.

I tossed away my parachute and Bayly climbed into the cockpit. I climbed in after him and using him as my seat, I proceeded to start my motor. It was with great relief that we heard the engine fire, and opening my throttle beyond all normal limits, I stood on the brakes until I had obtained full power, and then released them, and, as we surged forward, I extended a little flap. My handkerchief rushed up at an alarming rate, and we had not reached flying speed as we passed over it and down the slope of the wadi. Hauling the stick back a small fraction, I managed to ease the aircraft into the air, but we hit the other side of the wadi with a terrific thud. We were flung back into the air, still not really flying, and to my horror, I saw my port wheel rolling back below the trailing edge of the wing, in the dust stream. The next ridge loomed up and it looked as if it was to be curtains for us, as I could never clear it. I deliberately dropped my starboard wing to take the bounce on my remaining wheel, and eased the stick back just enough to avoid flicking. To my great relief we cleared the ridge and were flying.

Retracting my undercart and the small amount of take-off flap, we climbed up. I was shaking like a leaf and tried to talk to Bayly but noise would not permit. The remaining three aircraft formed up alongside me and we hared off for home, praying all the while that we would not be intercepted by enemy fighters, who should by now have been alerted. Luck remained with us, and we didn't see any enemy aircraft.

On nearing Marble Arch, I asked Squadron Leader Watt to fly beneath my aircraft to confirm that I had really lost a wheel and had not imagined it. He confirmed that my wheel had gone, but that the starboard wheel and undercart appeared to be intact. I then had to make up my mind as to whether to carry out a belly landing, thus damaging my aircraft further, or to try to attempt a one-wheel landing, which I thought I could do. We were at the time very short of aircraft and every machine counted.

The latter, of course, could be dangerous, so before making a final decision, I wrote a message on my map asking Bayly if he minded if I carried out a one-wheel landing. He read my message and nodded his agreement.

Calling up our ground control, I asked them to have an ambulance standing by, and told them that I intended coming in cross-wind with my port wing up-wind. Control queried my decision but accepted it.

I made a landing on my starboard wheel, keeping my wing up with aileron and, as I lost speed, I turned the aircraft slowly to the left, throwing the weight out. When I neared a complete wing stall, I kicked on hard port rudder and the aircraft turned further to port. Luck was with me and the aircraft remained balanced until it lost almost all speed. The port oleo leg suddenly touched the ground, and the machine completed a ground loop. The port flap was slightly damaged as was the wingtip. The propeller and the rest of the aircraft sustained no further damage. The port undercart was changed, the flap repaired, the holes patched up and the aircraft was flying again on the 27th of the month, only six days after Hun.

Every enemy aircraft on Hun was either destroyed or damaged. Six aircraft and one glider were burnt, and five other aircraft were badly damaged. The bag included two JU52s, two Savoia 79s, one JU88, one Messerschmitt 110, one CR42, one HS126 and two gliders. I was later to be awarded the DSO and this operation was mentioned as having a bearing on the award.

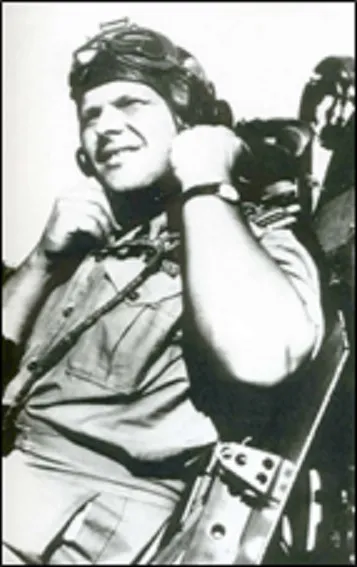

Royal Australian Air Force, Royal Air Force, No. 450 Squadron (RAF), No 3 Squadron (RAAF); Squadron Leader (later Wing Commander) Robert Henry Maxwell Gibbes, DSO, DFC and Bar, 450 Squadron RAF (later Commanding Officer 3 Squadron RAAF, and Wing Commander 80 Wing), wearing flying helmet, goggles, and flying jacket. Clay modelled and then plaster cast in London, 1943, the first edition of bronzes cast was in 1943 by Galizia Founders, London. After exhibition in the Royal Academy in 1944, one was sold to Bobby Gibbes. Another cast was sold to RAF Museum, Hendon, London. The Memorial's version is a unique cast of the second edition, 1968, cast on request, by Galizia Founders, London.

Bobby was discharged in 1946 before joining the Active Reserve in 1952 and serving at Townsville until April, 1957.

Bobby Gibbes loved flying and was the quintessential "Aussie larrikin". His two daughters Robyn and Julie paid tribute to their father's bold pioneering spirit. They told of their unique lives enriched by the experiences and adventures they were privy to with a trail-blazing father in the wilds of New Guinea. Bobby is survived by his wife of 62 years, Jeannie, [2007] his daughter Julie and Robyn and five grandchildren.

But Bobby's biography doesn't finish here for there is sufficient historical evidence for him to claim to be a descendant of the Duke of York albeit, an illegitimate one. John George Nathaniel Gibbes, born in 1787 raised in Barbados by an uncle was the offspring of the Duke who according to the history books abandoned his mistress and son.

John obviously enjoyed the benefits of his royal birth right, serving as Collector of Customs at Falmouth, Jamaica, and at Great Yarmouth on the Norfolk Coast of the UK. He and his family arrived in Sydney in April 1834. Now Colonel Gibbes, he served a record term of 25 years as the Collector of Customs.

The Colonel and his family came to be an intrinsic part of society in the new colony. He built a lavish house called "Wotonga" an aboriginal word for the Kirribilli area. The house and land were eventually sold to the Government in 1885 and considerably enlarged. Now known as Admiralty House, this superlative property currently fulfils a vice-regal function as the Sydney residence of the Governor-General of Australia.

There is a point to all this – a lavish portrait of Colonel Gibbes hangs in the drawing room at Admiralty House and a copy of a biography on Bobby Gibbes' "Sepik Pilot" by James Sinclair is ceremoniously kept on a bedside table in one of the main bedrooms. I leave you to make the genetic comparisons and to decide on the symbolism of the portrait and the book. [Editor]

One of my early recollections of dad was when my mother was in hospital in Goroka and dad and I had been visiting her. Dad then drove us back to the coffee plantation, Tremearne in Wahgi Valley, on his motorbike with me sitting in front on the petrol tank; a journey of about 10 hours.

At the age of around 4 years old dad would fly me in his SAAB to my one-teacher school in Banz every day, which was 22 miles from the coffee plantation. If he was away and mum had to drive me to school, the trip took over an hour one way on dirt, winding roads. Normally he would be delivering coffee or supplies, and I would be sitting on the bags of coffee along with our red kelpie, Paddy Gibbes. At times I would sit on his knee (there were no other seats on the plane), and he would teach me how to do a landing in the event of an emergency.

There were times when dad had to deliver supplies to plantations or remote missionary outposts where there was nowhere to land. Dad would tie mum and myself to the aircraft with rope so we could safely push the relevant supplies out of the aircraft at his instructions. The supplies were normally packed in 44-gallon drums which were shipped from Australia and collected by dad from the different coastal areas, and the hope was that nothing would burst on hitting the ground. Firstly, dad would fly low over the homestead and circle to let everyone know he was about to drop the supplies so they could warn all the locals that a drop was about to happen and for everyone to get out of the way.

During school holidays, I had the job of driving out to the strip to make sure there were no horses or pigs on the strip so he could land safely. Dad would fly low and circle the house to let us know he was coming in and it was time to go down and prepare the strip. If it was late, I would also have to line the strip with kerosene lamps to show him where the strip was.

Bobby is featured in the Temora Aviation Museum's Unsung Heroes project: Unsung Heroes - Bobby Gibbes